Jimmy Carter and advisors walking to Iran Hostage Crisis meeting, November 23, 1979, Library of Congress

FAILED NEGOTIATIONS

The first days of the hostage crisis were littered with attempts by the U.S. to construct

various compromises to deal with the conflict, although none succeeded.

various compromises to deal with the conflict, although none succeeded.

|

The morning of November 5, 1979, Carter dispatched envoys Ramsey Clark and William Miller to Tehran to deliver a letter to Iranian authorities from Carter requesting talks between the U.S. and Iran.

As soon as Clark and Miller departed for Iran, NBC broadcast news of their visit, and Khomeini denied them entry into Iran on November 6. "SPECIAL PRESIDENTIAL ENVOY LEAVES FOR IRAN." Nightly News, NBC, November 6, 1979, NBCUniversal Archives

|

Letter from Jimmy Carter to Ayatollah Khomeini, November 6, 1979, The George Washington University (Click to enlarge)

|

The Pentagon began devising a plan of military action for rescuing the hostages.

Deemed unlikely to succeed, it was considered an emergency plan.

Deemed unlikely to succeed, it was considered an emergency plan.

|

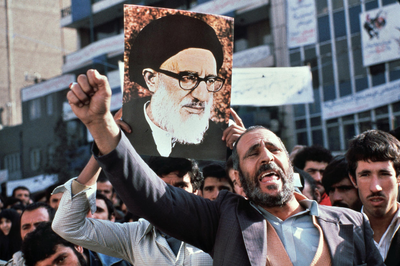

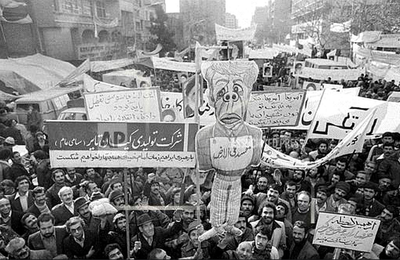

The Palestinian Liberation Organization (PLO) volunteered a delegation to arbitrate Iranian-American negotiations. The plan quickly faltered when the Iranian students refused this attempt at dialogue.

When thirteen women and African-American hostages were released on November 17, it was suspected but not confirmed that the PLO’s brief mediation effort led to the release. Released hostages at a press conference, Tehran, November 19, 1979

|

There was no reason to doubt that the PLO was instrumental in arranging this partial release….Publicly the PLO took no credit for the release and seemed chastened by the experience. My own impression, based on subsequent events, was that the PLO had to expend far more political capital than intended, even for this limited result….In any event, the intimacy of Iranian-PLO relations seemed to subside after this episode, and the PLO never again volunteered to intercede. The real lesson of this initial approach to Khomeini–by an intermediary with impeccable revolutionary credentials–was to demonstrate the difficulty of persuading Khomeini to alter his course of action. A sick hostage, Richard Queen, was released July 11, 1980. Fifty-two hostages would remain for the entirety of the 444 day crisis.

|

Even U.N. Security General Kurt Waldheim was not permitted to meet with Khomeini or the hostages

upon visiting Tehran in December 1979 and January 1980.

upon visiting Tehran in December 1979 and January 1980.

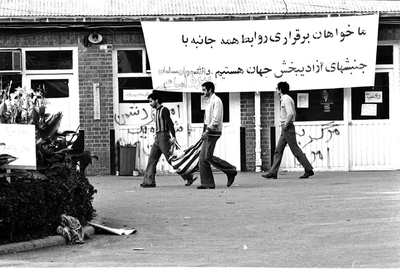

Protests against Kurt Waldheim's visit to U.S. Embassy, Tehran, January 5, 1980, AP Archive

|

Starting in January 1980, White House Chief of Staff Hamilton Jordan continuously met with French lawyer Christian Bourguet and Argentinian businessman Hector Villalon to create a United Nations commission that would listen to Iranians’ grievances against the shah and issue a report. Afterward, the hostages would be released.

On February 23, 1980, in a radio speech, Khomeini declared that only the Revolutionary Council, President Bani-Sadr, and the Majlis, the not yet elected parliament, would be permitted to discuss the release of the hostages.

From the first commission was a body born of despair, nurtured by frustration, and fueled by the absence of any alternative. Ham, they are crazy. |

Article from The New York TImes on Hector Villalon's involvement in hostage negotiations, April 1, 1980, The New York Times

|

|

Widespread criticism of Carter’s failure to compromise or take military action for fear of causing harm to the hostages threatened his hopes of re-election.

I hope we never have to choose between the hostages and our nation's honor in the world, but, Mr. President....If they're still in captivity at Thanksgiving, what will that say about your presidency and America's image in the world? Carter-Mondale re-election poster, Lori Ferber Collectibles

|

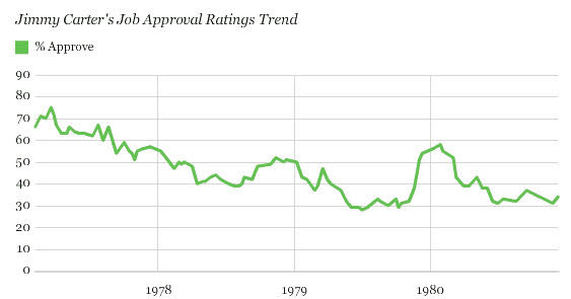

Jimmy Carter's presidential approval rating, Gallup

Those who suggested that Carter artificially "hyped" the hostage crisis for his own political benefit got it exactly backwards. President Carter initially benefited from the hostage crisis, as presidents almost always gain public support in a national crisis, and he was quite prepared to make the most of it. However, a more cautious politician, realizing the dangers of failure, would rather quickly have attempted to disassociate himself from the consequences and would have been more inclined to adopt the kind of damage-limiting strategy that later had such appeal to pundits and academic observers. To the best of my knowledge, President Carter never seriously considered such a strategy, and that, again, was characteristic of the man. |